Here is a word from Kate Darnell, one of the featured artists of Words & Afterwards. The exhibit continues to be open through June 24, at (SCENE) Metrospace of East Lansing, 110 Charles Street.

This project both motivated and supported the start of a series of pieces that I have been thinking on for some time, and hope to expand into a larger body of work.

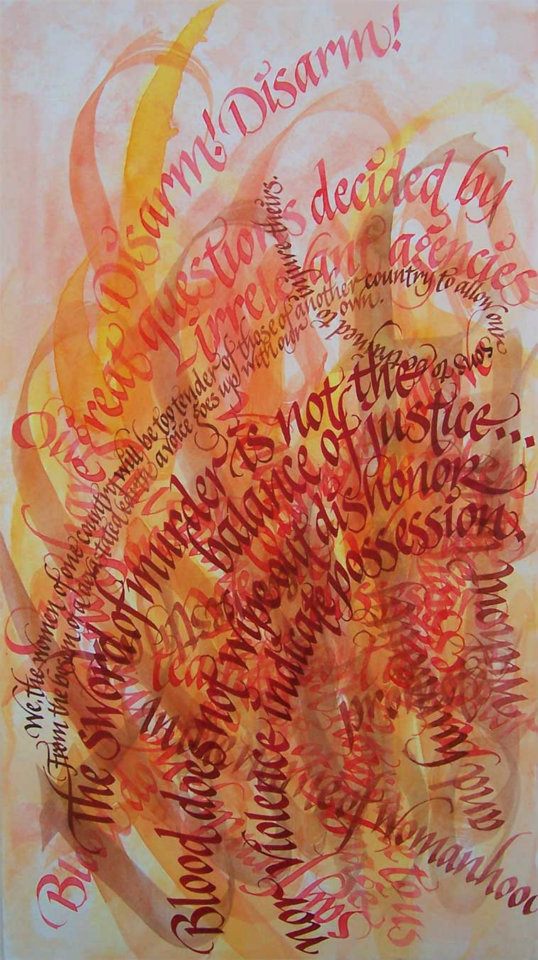

The creation of several calligraphic paintings based on a theme of non-violence and hope has kept me considering and reconsidering the idea of words as both literal meaning and visual image. It has also allowed me to put my convictions (and also questions) about the tragedy and futility of war into my art in a way that I hope is both conceptually clear and visually beautiful.

The notion that words can be used as both written utterance and as visual rhythms and color is nothing new, but for a calligrapher accustomed to creating more traditional pages, and an artist whose work is generally not abstract or overtly topical, breaking away from convention has been creatively stimulating and liberating.

Tragedy, violence and suffering in art and poetry are also nothing new, and it has always been a difficult notion that we can call such imagery “beautiful”. William Butler Yeats wrote of a “terrible beauty” in his poem about the 1916 Easter uprising against the British in Ireland, and this phrase has often been used to describe art that deals with war and other horrible unlovely acts of violence. But poetry and art help us make sense of our world. Beautiful sounds and exquisitely composed images can comfort, condemn and mourn, as well as praise or celebrate.

Art and poetry are complex and really well-suited to express the ambiguities and contradictions that will always exist in our feelings about war. Honoring these tangled knots — the coupled contrasts of heroism and brutality, victory and loss or the deeply personal — in the midst of the powerful collective experience, is delicate business. However, a short poem or painting may be a more complete story than detailed descriptions of fact by journalists, politicians or writers of history. Art can help us move beyond the overly simple anecdote or the jingoism of propaganda, to see deeper and think carefully. (I say this with full knowledge that art and poetry also can and always has been used as propaganda).

The very act of creating a piece of art with a horrific subject can also be an act of hope, as part of the grace in expressions of “terrible beauty” is the sense of truth that we experience in such work. For the artist there is the satisfaction or catharsis of using their “voice” to acknowledge or witness. For the reader or viewer there is the rush of recognition; here is something of our own experience or awareness or thought. Here is affirmation or revelation vividly expressed in a way that makes us weep, sets the hairs on the back of our neck to rise, or just lets us know we are not alone.

This was my response to the poetry I used in my calligraphic paintings, and I hope that my interpretations do those poets’ words justice.

Recent Comments